Freddie Mercury, the legendary vocalist of Queen, has definitely made his mark in the annals of history. His story has been so inspiring and tragic at the same time. Born in Zanzibar, studied in India, away from his home for the most of his life, battling with his sexuality, superstardom with Queen and then finally getting diagnosed with AIDS. That too at a time where the disease was a black box and a death sentence in one, carried a lot of stigma and caused a lot of discrimination against the people suffering from it.

A lot of people wanted to understand more about his heartbreaking journey after he was diagnosed, but information is very very difficult to come by. We have researched hundreds of interviews, documentaries, blogs, media articles, accounts from his close friends and family to compile this article so that we as fans can take courage from his incredible journey and get inspired by it.

Before the World Knew

For most people, Freddie Mercury’s death on 24th November 1991 exists as a moment frozen in time.

- The previous day, a short statement was released late in the evening.

- A confirmation that the world had been speculating about and dreading for years.

- And then, less than a day later, the news that he was gone.

What rarely enters the conversation is the life that unfolded quietly before that moment. Not the performances or the mythology, but the years Freddie Mercury spent living with HIV while continuing to work, to host friends, to record music, and to decide, very carefully, how much of his private reality the world would ever be allowed to see.

This is not a story about secrecy for its own sake. It is a story about control. About how Freddie chose to live once he understood his time was limited, and how he faced the end with clarity rather than fear.

When nothing seemed wrong

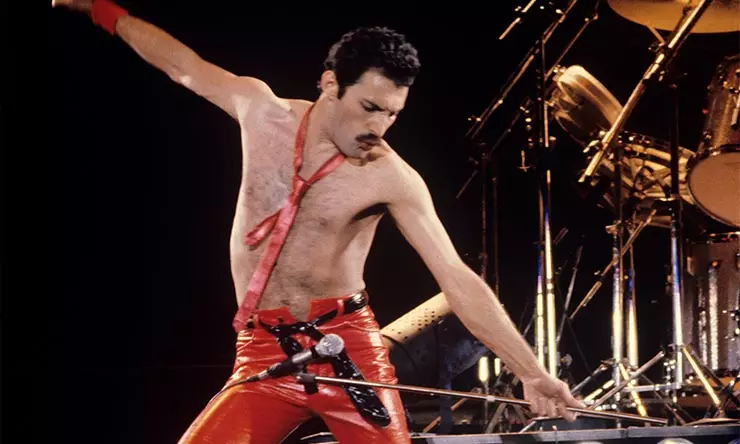

By most medical understanding, Freddie Mercury was likely HIV positive by the late 1970s/early 1980s. Yet for years, there was nothing outward to suggest it. He toured relentlessly, recorded constantly, and performed with the same physical commitment that had always defined him.

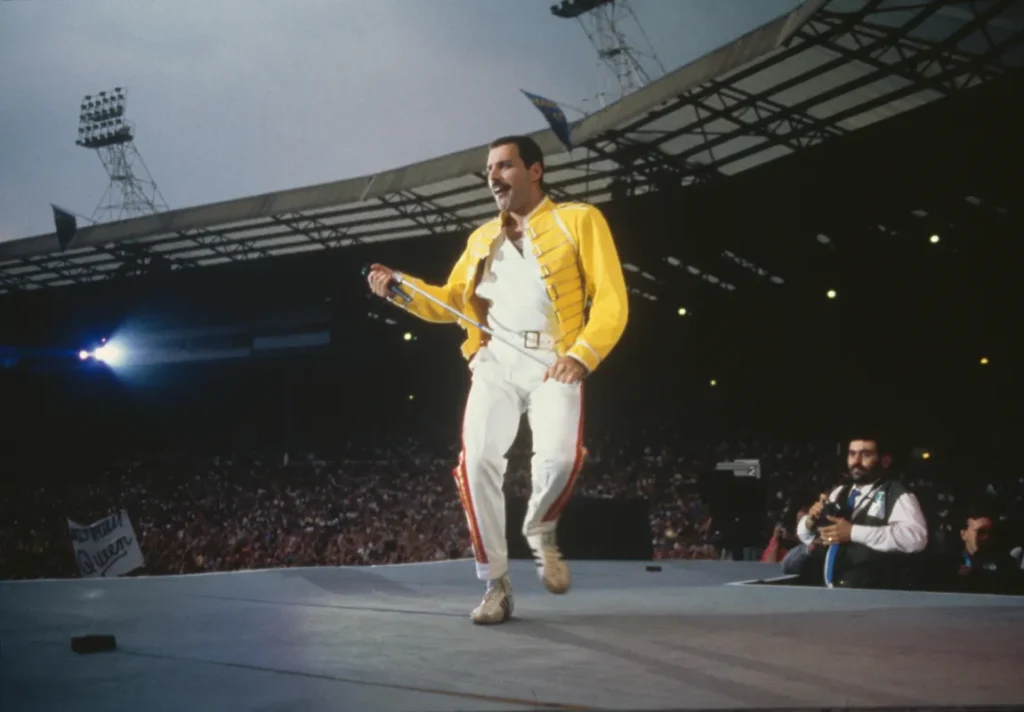

Even now, people rewatch Live Aid in 1985 looking for signs, slowing down footage, searching his face and movements for clues. At the time, there were none.

Knowing how HIV progresses, he was technically already ill. But in every way that mattered to him day to day, he still felt like himself.

It was only toward the end of the Magic Tour in 1986 that fatigue began to creep in. Even then, it did not feel alarming. The tours were longer, the venues significantly larger, and he still insisted on covering the entire stage. Feeling tired seemed like a reasonable consequence of scale rather than a warning sign. He never complained of pain. He never spoke of illness.

“The Magic Tour took a lot out of Freddie. After Knebworth he said, ‘I can’t do this anymore.” Brain May shared in the BBC documentary about Queen

Suspecting, but not wanting to know

By the mid 1980s, HIV and AIDS were no longer distant headlines. Friends were getting sick. Some were dying. Conversations about the disease happened quietly, particularly while touring in the United States. Like many people at the time, Freddie was aware of what was happening but carried the private belief that it would not happen to him.

That belief began to fracture in early 1987, when a dark lesion appeared on his hand.

A biopsy was taken. When the results came back, it showed Kaposi’s sarcoma, a condition already closely linked to AIDS. From there, further tests followed, and with them came the confirmation that neither Freddie nor those around him had been ready to hear.

Freddie avoided taking the doctor’s call. He did not want the words spoken aloud. It was Mary Austin who eventually persuaded him to listen. By the spring of 1987, there was no room left for doubt.

He did not react with panic. He did not gather people around him to explain. He told only those who needed to know, including the small group of people living with him at Garden Lodge. The decision was practical as much as emotional. He wanted honesty at home, and he wanted to protect everyone else, including himself, from the intrusion and noise that public knowledge would bring.

“Yes, I did know. I was one of the few who were told this fact. Freddie found me alone in the kitchen at Garden Lodge and told me himself not too long after he had learnt the bad news in Spring 1987. He told very few people because he wanted to protect his family and friends from press intrusion. I think he felt he should tell us in the house as we would have close contact with him and just wanted us to feel safe and take care.”

Peter ‘Phoebe’ Freestone, Freddie’s PA from 1979-91

Living with the diagnosis

What followed was not withdrawal or depression. It was concentration. The diagnosis seemed to shine a light on what Freddie wanted out of life and music and he put forward all of his efforts there.

Freddie understood what an AIDS diagnosis meant in the late 1980s. Treatment options were limited. Outcomes were uncertain. Time, suddenly, had shape. Instead of surrendering to it, he chose to live deliberately inside it.

He continued working. He continued recording. He avoided the kind of sympathy that slowly turns living people into symbols of decline.

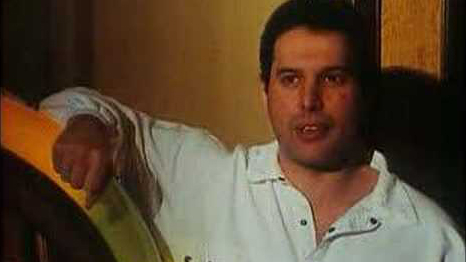

David Wigg, the British journalist who interviewed Freddie in the late 1980s, quotes from an interview he conducted with Freddie, on the effect the AIDS pandemic had had on his lifestyle

“I’ve stopped going out,” Mercury said. “I’ve almost become a nun. I thought sex was very important to me… I lived through sex… now I’ve just gone completely the other way. It’s frightened me to death. I’ve just stopped having sex. For me sex was an integral ingredient in what I was doing. It was excess in every direction. But I don’t miss it.”

And then Wigg’s recollection of what Freddie said after the tape stopped recording:

“He said, ‘I’m going to fight it… We’re going to find a cure.”

He was not ashamed of his illness. Those closest to him would later say that embarrassment and shame never entered his thinking. What he wanted was normality. He wanted to live what remained of his life, not sit under the weight of pity or watch himself fade under public scrutiny.

Doctors advised changes. In 1989, he largely stopped smoking and drinking, not because he wanted to reinvent himself, but because it might give him more time. He did not quit entirely, but the habits were curtailed. Cigarettes were confined to moments of pressure in the studio. At home, they disappeared.

In longer recollections, Phoebe explains that by late 1989 Freddie’s health had declined enough that medical professionals privately warned the inner circle that he might not survive much longer, potentially not even to the end of that year. However, Freddie continued working, recording, and living at Garden Lodge well beyond that prediction.

“In 1989 the doctors said Freddie wouldn’t see Christmas. But Freddie proved them wrong.”

Hospital visits were handled quietly. When he needed X ray treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma or the placement of a central line, he entered through back doors, early in the morning, avoiding recognition. Illness was managed carefully, almost administratively, without allowing it to spill into the rest of his life.

The Medications

After his diagnosis, Freddie did not turn away from treatment. But he knew that chances of a complete recovery were slim, and did not place his faith in it.

In the late 1980s, the options available to people living with HIV were few, experimental, and often punishing. The drugs came with heavy side effects and uncertain benefits, offering at best the possibility of slowing what could not yet be stopped. Freddie understood this clearly. He did not talk about recovery, and he did not expect a reversal of what was happening to him.

Still, he tried what was available.

Those close to him have said that Freddie approached these treatments without illusion. He knew they were unlikely to change his own outcome, but he also understood that progress depended on people being willing to take part before results were guaranteed. If nothing else, the effort might help doctors learn something that could matter later.

As time passed, the toll of the medication grew harder to ignore. The physical cost increased, while the benefits became less certain. Gradually, treatment stopped feeling like a way of holding on to life and began to feel like something that was eroding what remained of it.

When that balance tipped, Freddie did not dramatise the moment. He simply made a decision about how he wanted the time he had left to feel.

“I believe he was at peace with himself. Freddie decided to stop his medication on his own terms. He knew the consequences of his actions and had the time then to talk with friends and family and say his goodbyes. No-one knew how much time he had left on the 10th November, but he must have understood his body and what it was feeling as the days passed. He made all his arrangements and sorted out the statement to the world during those two weeks, and I think he just felt and knew it was his time.”

Peter ‘Phoebe’ Freestone

When the body began to change

At home, the changes were subtle at first.

Freddie had never been a big eater, but as the illness progressed, his appetite diminished further. Strong flavours became difficult to tolerate. Meals became simpler. Food became something to sustain him rather than something to enjoy.

Even so, he continued hosting friends, guiding conversations at the table, ensuring everyone else was comfortable, expertly disguising how little he himself consumed. Normality mattered to him, and he protected it wherever he could.

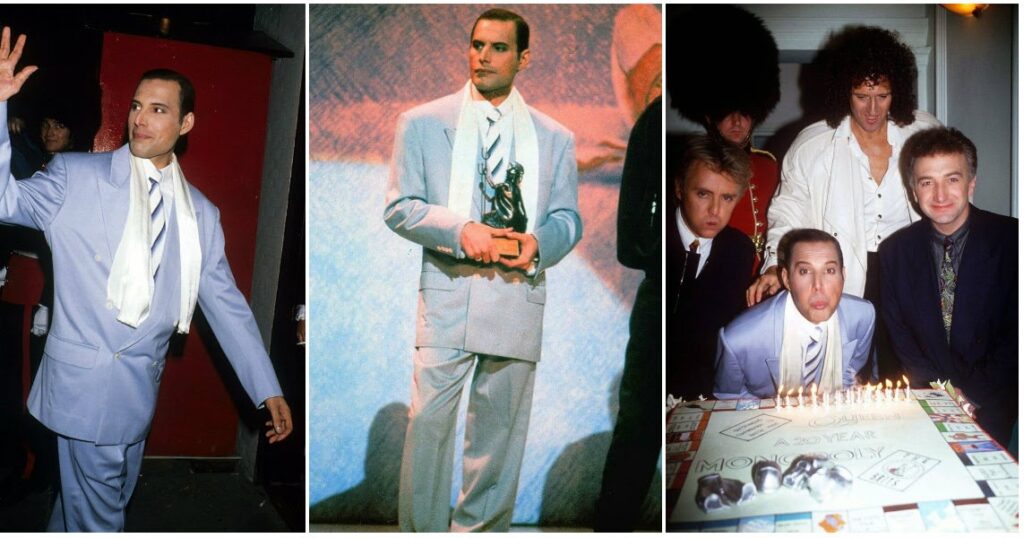

By 1990, that normality became harder to maintain.

At the Brit Awards that year, the physical changes were impossible to ignore. Freddie was visibly thinner. His face had altered. Those who saw him did not know for certain that he was ill, but many suspected something serious. Friends recognized familiar signs from others they had lost. Others simply sensed that something was wrong.

Music broadcaster Paul Gambaccini later commented on the visible shift in Freddie’s appearance during that era. In retrospective interviews about the late 80s, he shared:

“It was clear something was wrong.”

The press moved faster than certainty. Rumours hardened into accusation.

Freddie said nothing.

Recording against time

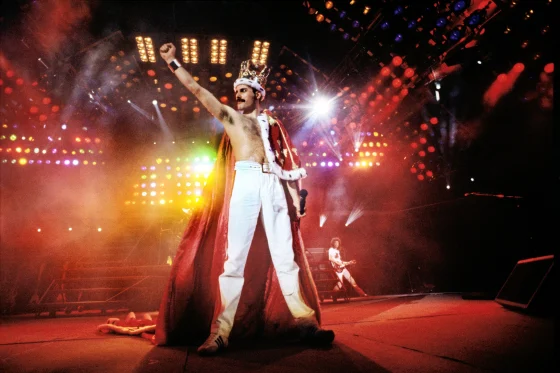

As his physical strength declined, his urgency sharpened. Recording became the priority.

He knew he would not live to finish everything. What mattered was leaving material behind. Vocals that could be shaped later. Fragments that could become songs after he was gone.

Brian May later remembered Freddie saying, “Write me stuff. I know I don’t have very long. Keep giving me things I will sing, then you can do what you like with it afterwards.”

There was one instruction he repeated without compromise.

“You can do what you want with my music,” he told Jim Beach, “but do not make me boring.”

During the recording of The Show Must Go On, Brian May hesitated, worried that the song might be too demanding. Freddie brushed the concern aside. “I’ll do it, darling,” he said, downed vodka, and delivered the vocal in a single take.

“Freddie was in immense pain at that time, he could not even sit properly. I said, ‘Fred, I don’t know if this is going to be possible to sing.’ And he said, ‘I’ll fucking do it, darling.’ Vodka down… and went in and killed it, completely lacerated that vocal.”

Brain May recalls in a BBC Documentary

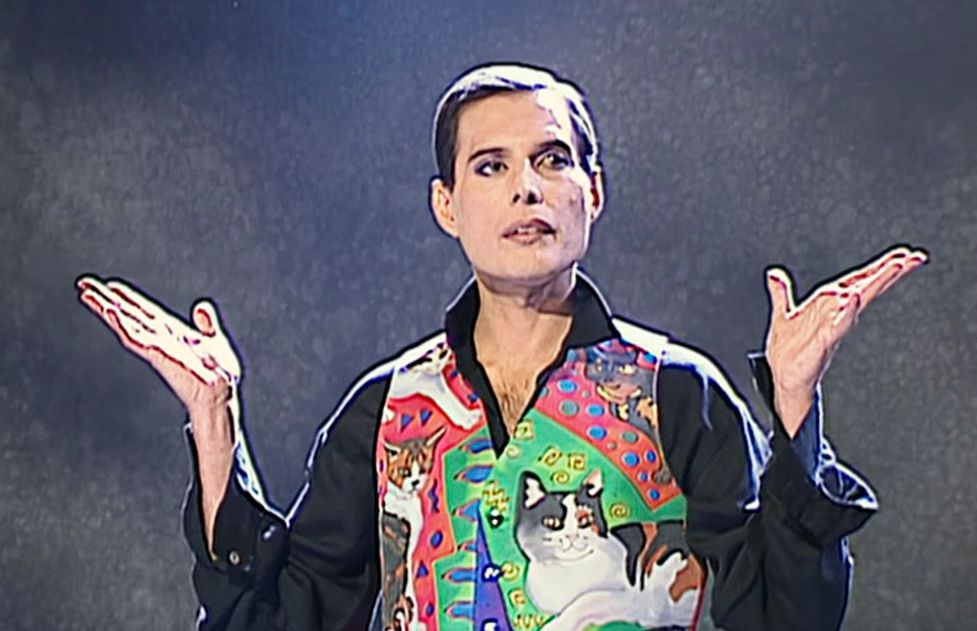

By mid 1991, recording sessions became sporadic, dictated by what his body would allow. Still, during stays in Montreux, he returned to the studio whenever he could. His last appearance was in the music video of ‘These are the Days of Our Lives’. He ends the video with a sly look at the camera and a heartfelt ‘I still love you’ to his fans.

Life inside Garden Lodge

By November, Freddie’s world narrowed almost entirely to Garden Lodge.

He ate and drank very little. His strength faded daily. Even so, he was still able to stand and walk short distances with assistance.

On November 20, he asked to be taken downstairs one final time. He wanted to see his artwork. Carried down the stairs, he walked slowly through the sitting room and Japanese room, supported by those around him, commenting quietly on when he had acquired certain pieces.

The house was calm. Familiar. Safe. Elton John has spoken openly about visiting Freddie in the final months of his life.

“He was very ill, but he was still Freddie. He was still laughing and still making jokes.” Elton John recalls in his biography ‘Me’

In the final two weeks of his life, music largely disappeared from the house. The television stayed on instead, more as company than entertainment. Friends and loved ones remained with him around the clock.

Jim Hutton, Freddie’s partner for the past 6 years, later recalled those nights as quiet and gentle, spent talking about inconsequential things, lying together, unafraid.

Telling the World, Carefully and at the Very End

By the final week of his life, Freddie understood that silence could no longer hold.

The rumours had grown too loud. Much of the story had already been written in fragments. What remained was deciding how, and when, the truth would finally be acknowledged.

On Friday, November 22, Freddie asked Jim Beach to come to Garden Lodge. They spoke for hours in Freddie’s bedroom, discussing timing, wording, and consequence. Freddie knew exactly what would follow once the statement was released.

When the wording had been agreed upon, Jim Beach came downstairs and told those in the house what Freddie had decided. They were warned to prepare for what would come next.

That evening, at eight o’clock, the statement was released.

It was brief and controlled. Freddie Mercury confirmed that he had AIDS.

Less than twenty four hours later, he was gone.

The final decision

In his final days, Freddie chose to stop his medication. It was his decision, made with full understanding of what it meant.

He used the time that followed to put his affairs in order and to say his goodbyes. On Friday, November 22, he asked Jim Beach to come to Garden Lodge. They spoke for hours. Together, they finalised the statement that would confirm publicly what Freddie had lived with privately for years.

The statement was released that evening. In the days that followed, Brian May wrote to the Queen Fan Club on behalf of the band. In that letter, he made something clear that only became fully visible after Freddie was gone. The announcement had not been a surrender.

“His announcement, made by his own will only when he knew his fight was over,” Brian wrote, “will, with our help and yours, be a major factor in persuading the public that AIDS is now EVERYONE’S problem.”

Less than twenty four hours later, Freddie Mercury died at home, from bronchial pneumonia caused by complications related to AIDS.

Those closest to him believe he was at peace.

The charity and support that was hidden from the public

Freddie Mercury never spoke publicly about supporting AIDS research. He never attached his name to campaigns, never stood at podiums, never allowed his illness to become something he represented.

That silence did not mean inaction.

In the final years of his life, Freddie quietly donated significant sums to HIV and AIDS charities through third parties. The choice was deliberate. He did not want attention drawn to the act, and he did not want his illness reframed as activism. What mattered to him was that the support reached the right places, not that it was seen.

Those closest to him later confirmed that these donations were made regularly, particularly during the last four years of his life. They were handled discreetly, in the same manner he handled most things connected to his health.

Freddie did not believe these contributions would change his own future. If anything, they reflected a longer view. If knowledge could accumulate, if treatment could improve, if someone else might be spared what he was facing, then the effort felt worthwhile.