As Philippe Besson welcomes the readers into the backdrop of Lie With Me—small, unknown, Barbezieux in Southwestern France—he reiterates that he is “from a bygone era, a dying city, a past without glory’. This sets the scene: a past buried in the back of his mind; a dying city (and people in it) that still haunts him.

Lie With Me is perhaps enriched by the mystery of its origin; is it fiction? Memoir? Our narrator is unnamed, but he carries all the well-known and less-known aspects of Philippe Besson. He talks about his books, some of which got adapted into movies (like the adaptation of Besson’s second novel Son Frère by French author Patrice Chéreau), and he resides in the same small town. Yet the biggest connection to autofiction stems from the dedication at the start of the novel: in memory of Thomas Andrieu (1966–2016).

Amongst all speculation, one thing that shines through is that the story, following one of the most important periods of the narrator’s (or Besson’s) life, is not just a tale of adolescent first love for a queer youth, but the narration of stifling silence and its adverse effects. Growing up in a small town in the 1980s as an outcast, his queer identity is a shell he eventually grows out of through acceptance. Yet, the novel reminds us that there are some who never do.

The roots of regret and loss

The novel begins as our outcast narrator lives a carefree and unaware life under the quiet authority of his father. He admires a fellow schoolmate, Thomas Andrieu, but only from afar. He is fully accepting of his homosexual identity but also aware of its illicit nature. This awareness still does not prepare him for when Thomas himself reaches out to him. This gives way to a series of encounters that seem shallow and infatuation-fueled at first but slowly develop into more.

Herein comes the loss and regret. Thomas’ singularity is attractive to the narrator, but approaching him is impossible. In provincial France in the 1980s, being open about his identity was out of the question. All their encounters are in secret, and when the narrator inquires, ‘Why me?’ Thomas relays, ‘Because you will leave and we will stay’.

The sentence is significant because it sets the foundation of the story. Thomas only gets over his fear of his queer identity and approaches the narrator because he sees this encounter as a one-time opportunity. He refuses to accept that this could be his reality. This is also where Besson brings in the class divide between them. The writer comes from an upper-middle-class background with accepting parents.

“I was lucky to have liberal, loving, and understanding parents; I didn’t think the revelation [of my sexuality] would be a problem for them. At first, I had this intuition it wouldn’t go too badly, and it didn’t,” Besson relayed in an interview.

Thomas, on the other hand, is the son of a farmer and a mother who is a rigorous Catholic. His future of hard labour and heteronormative life is set in stone. He also has a younger sister with Down syndrome, whom he cares for alone.

The stifling trauma of silence

All this difference only highlights the regret that comes after. Thomas keeps himself in a shell and refuses to believe there is a way out; his answer to his own identity is silence. This mentality does not even leave him years later, when he abandons his wife and family to ‘live his own life’. It stays with him as he eventually ends his own life.

“In the end, he remained hidden all his life. In spite of the great departure, the ambitious effort to forge a new existence, he fell back into all the same traps: shame, the impossibility of sharing a love that endures,” says the narrator.

Another important part of the novel is the impact of loss at a young age. After the narrator and Thomas part ways, the narrator traces Thomas’ character in every novel he writes. He recounts the loss he felt as he lost friends and loved ones during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Though the affair takes place before the peak of the crisis and lasts only in the course of one summer, it still leaves a lasting effect that culminates in the narrator finally writing this novel.

“He realised that all of his other books had been half-conscious efforts to “evoke absence, disappearance, and the mourning of love,” and that he’d been spinning around the axis of Thomas Andrieu, a main character in the book and its honoree, for twenty years,” observes Lauren Collins in an article in The New Yorker.

The French title of Lie With Me is Arrête avec tes mensonges, directly translates into ‘Stop with your lies’. The title has a two-fold connection. Young Besson’s mother admonishing him for always making up stories and ‘lies’ and older Besson’s acceptance of letting Thomas lie to and with him.

A simple expression

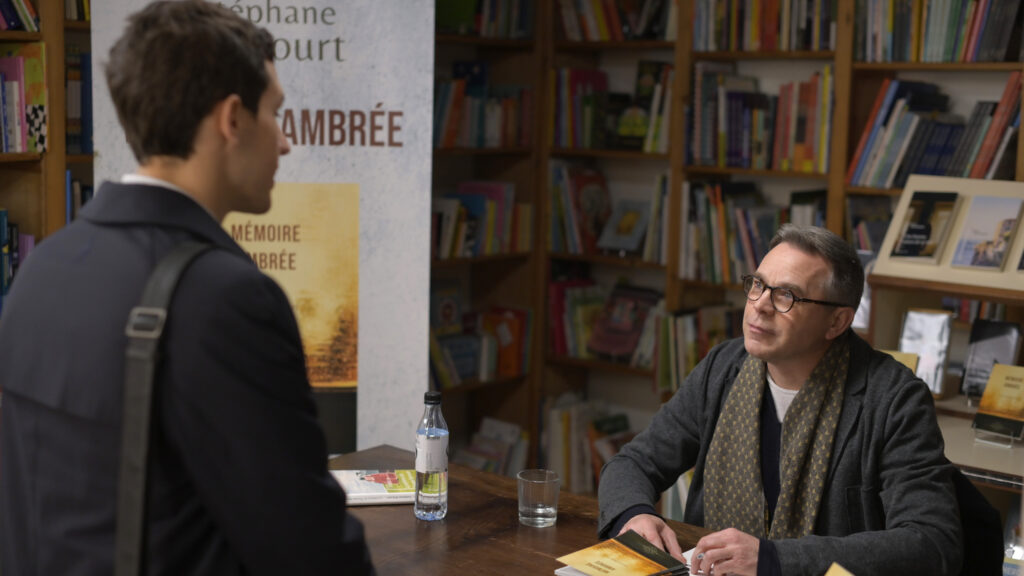

What sets Philippe Besson’s Lie With Me apart from others is the simple language in which it is conveyed. The tale of love, loss, and identity was an immediate No. 1 bestseller in France and went on to win multiple accolades. When Molly Ringwald translated the novel, she relayed how she wanted to exactly catch the simplicity of it. “I loved his minimalism and how sort of matter-of-fact he was.”

Despite its simplicity, its impact on the writer was remarkable. “When I finished, it was a terrible moment,” Besson said. “I didn’t see how I could write novels again. I asked myself, ‘What’s the point, now, of writing a novel?’

Yet like his persona in the novel, he accepted the painful reality and went on to write “Un Personnage de Roman” about his close friend and French President Emmanuel Macron. His simple expression relays the painful nature of queer identity and explores the adverse effects of choosing to live in silence; but at the same time, it does not label people like Thomas (who still exist in nations all around the world) as cowardly. His narration is one of understanding.

“I think of all the men I met in bookstores, men who confided in me about having lied for years and years before finally resolving to leave everything to start all over again (they will recognise themselves if they read these lines). Thomas never found his courage. I say “courage,” but it may be something else. Those who have not taken this step, who have not come to terms with themselves, are not necessarily frightened; they are perhaps helpless, disoriented, lost as one is in the middle of a forest that’s too dark or dense or vast,” shares the narrator.

Join The Story Watch’s initiative to create a vibrant community for the startup ecosystem.